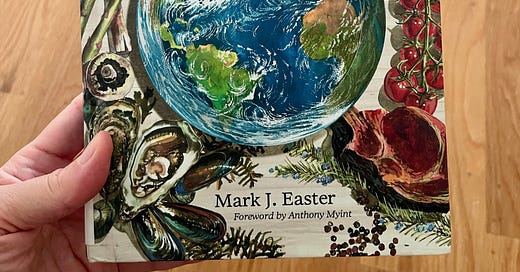

In The Blue Plate: A Food Lover’s Guide to Climate Chaos, ecologist Mark J Easter analyzes the environmental impact of foods that typically grace an American table: bread, vegetables, seafood, meat, fruit and dairy. Most of our food supply has been produced “conventionally” in an intensive, industrial system, with a large carbon footprint. But for each food, Easter also features farmers and producers who have implemented innovative solutions to make America’s favorite foods more sustainable. If you suffer from “analysis paralysis” while shopping for dinner, you’ll find answers in this inspiring book.

While every chapter is a page-turner, I want to focus on the dairy chapter and later, offer some recipe ideas for ensuring no milk goes to waste.

The problem

1) One quarter of emissions from dairy cows come from growing, transporting and processing their feed. Each cow eats 80 to 120 pounds of forage per day!

2) Cows produce huge amounts of methane when digesting grass in their rumen, “basically a methane factory.” The cows’ methane burps emit about a quarter of milk’s emissions.

3) Around another quarter of dairy’s emissions comes from the energy consumed to operate the dairy, ship the milk for processing and packaging (plus the actual processing and packaging) and ship the final produce to the retailer.

4) The last quarter of emissions comes from modern poop management.

The CAFO

Before the 1960s, a dairy might include dozens of cows living—and pooping—outside. When the cows temporarily moved indoors during inclement weather, farmers would gather their herd’s manure to spread on fields, burn for fuel or build with. Today, in an industrial dairy, hundreds of cows live indoors year-round, confined in a CAFO (concentrated animal feed operation).

As the new dairy CAFOs appeared, municipal sewage plants couldn’t handle the manure. Easter writes “A modern dairy today milking one thousand cows produces as much manure as a town of sixty thousand people.” So dairies dug ponds on site and piped the manure into them. The bacteria that break down that manure do so anaerobically (without oxygen) and emit massive amounts of methane as a byproduct. (Methane, a greenhouse gas, is 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide.)

Easter visits a dairy that has taken steps to reduce its carbon footprint, Straus Family Creamery, here in Northern California. The dairy puts its cows on pasture whenever possible, recycling manure into the soil. It has planted windbreaks and pasture borders with native plants, protecting the livestock and reducing erosion along the dairy’s waterways. It was the first dairy in the US to install an anaerobic digester, which captures manure methane and burns it to power the dairy.

Even with such innovations (many of which my grandparents would recognize), milk still makes a large carbon footprint. Given that footprint, if, like me, you consume dairy, you won’t want any going to waste. The following ideas will help.

Ferment the milk

Fermentation renders milk less perishable and extends its shelf-life. While a hard cheese may ferment for years, the fermented foods below will be ready to consume within a day.

Yogurt

To make yogurt, heat milk to 180°F, cool it to 110°F, stir in a small amount of yogurt with live cultures and wait. Technically you can repeat this cycle indefinitely unless a) you accidentally eat all the yogurt and have none left to make more or b) your yogurt culture dies. Go here for the full yogurt-making instructions.

Cultured buttermilk

As with yogurt, you’ll need a bit of buttermilk to make buttermilk. Cultured buttermilk acts as a starter, like sourdough starter or ginger bug. You’ll have to feed and nurture it to keep alive. So you’ll need to acquire some cultured buttermilk first. Make sure you buy cultured buttermilk not flavored buttermilk. The ingredient list on the package will include “live cultures.” After you make buttermilk with your excess milk and small amount of acquired buttermilk, you can keep the culture going. Go here for the directions.

n.b. This differs from quick buttermilk, which provides another good way to use up excess milk. More on that coming up.

Sour cream

You’ll need the cultured buttermilk above to make sour cream. Into a jar, stir ¼ cup of cultured buttermilk into 1 cup of half and half. Let the jar sit at room temperature for a day. Chill. Enjoy.

Crème fraîche

Following the method above, use heavy cream instead of half and half to make fabulous crème fraîche.

Make soft cheese

You’ll want to eat these cheeses quickly. That won’t be a problem because they taste delicious. Save the whey for baking bread or pizza.

Ricotta

So easy and so good. You’ll heat milk and cultured buttermilk, wait for the curds to sink and strain them out. Go here for the full recipe.

Paneer

To make paneer, curdle the milk with an acid, strain the whey and with the curds, form a brick (or a blob if, like me, you don’t have fancy equipment). Go here for the recipe.

Bake something

I can’t possibly list everything here! Some ideas: blueberry muffins, brioche, popovers, french toast, rice pudding, bread pudding…

Cook something

Make scalloped potatoes or savory bread pudding. Whip up béchamel sauce that you can then use as a base for macaroni and cheese, pot pies, creamy vegetable soup and more.

Freeze it

Either freeze the milk to use later or make sherbet with it. Sherbet is like a light ice cream made with milk, not cream, and lots of fruit or fruit juice. And you don’t need an ice cream maker to make it! (This recipe looks good.)

Drink it

Okay, you probably thought of that already but you could incorporate the milk into a glass of mango lassi or a cup of hot chocolate. Blend the milk with ice cream (or the sherbet above) for a milkshake.

Or make a quick buttermilk to drink (or to bake with). For 1 cup of buttermilk, place 1 tablespoon of lemon juice or vinegar into a measuring cup. Fill the cup up to the 1-cup line with milk. Let sit for 5 minutes to curdle. (This is NOT cultured buttermilk so don’t try to ferment anything with it.)

Make milk alternatives

Perhaps you’re still ruminating on cow burps and manure lagoons. You may want to try making your own milk alternatives. You’ll also skip plastic-lined Tetra Paks, make a tastier product and save money. A few to try:

If you make any of these, you’ll be left with pulp. Mixing some into a batch of granola makes quick work of it. (Go here for a granola recipe.)

And just tonight I am wondering how to “save” the soft goat cheese that may or may not be good after today. Freeze it?

I've used your method for making yogurt, but I've always wondered why it is necessary to take fresh milk straight out of its container and heat it to 180 degrees. Wouldn't the process work as well just warming it up to 110 degrees?